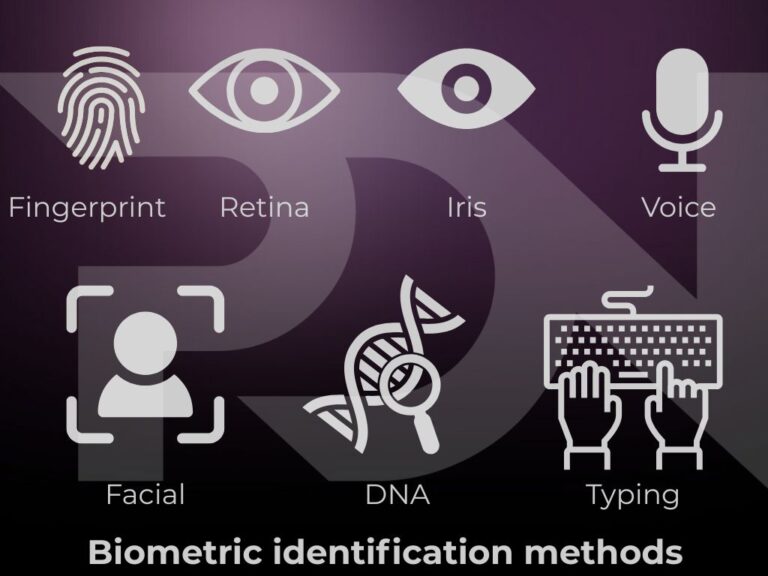

Biometrics—automatic recognition of fingerprints, irises, faces, voices, palm prints, behavioral signatures, etc.—have become a pillar of authentication in our digital and physical lives. The promise of biometrics is clear: simpler, faster, and often more secure than passwords.

But this promise hides a fundamental vulnerability: biometric data is irreplaceable. If a password is leaked, or if it has been used for too long, it can be changed. But you cannot change your fingerprint or the structure of your iris. It is this irrevocability that makes the compromise of biometric data particularly dangerous.

First, it is essential to differentiate between two categories of attacks, that can be combined.

Biometric data has high commercial and operational value.

The protection of biometric data presents unique challenges. Unlike passwords, which can be encrypted and then replaced if leaked, fingerprints, faces, and voices are based on immutable physical characteristics. Biometric templates, the digital representations created from the capture, often contain correlated or partially reconstructible elements. If poorly protected, they become a prime target for cybercriminals.

Inadequate storage, for example in the form of raw images or unencrypted templates, turns any biometric database into a treasure trove for an attacker. Even when models are encrypted, they must be temporarily decrypted for comparison. This step creates a vulnerability: a compromised server, a falsified authentication module, or a software flaw can then expose the entire system.

These threats are now growing with the rise of artificial intelligence. Image, sound, and fingerprint generation technologies can now produce credible faces, convincing artificial voices, or partial fingerprints capable of fooling certain devices. In addition, more technical attacks directly target the learning systems used for biometric authentication: extracting information from models, identifying data used during training, or deliberately poisoning learning sets. These techniques jeopardize the reliability and confidentiality of biometric solutions.

Facial recognition technologies and, more broadly, biometric systems are not neutral. Numerous studies have shown that their performance varies depending on demographic groups: skin color, age, gender, or ethnic origin. These biases amplify the risks of injustice and discrimination. In the event of a massive leak, already overexposed populations become the first victims: their data can be used to increase surveillance, fuel profiling practices, or facilitate digital harassment.

These threats are not fictional. In 2015, the hacking of the Office of Personnel Management (OPM) in the United States compromised the fingerprints of more than 5.6 million federal employees. Four years later, in 2019, the “Biostar 2” database, used for physical access control, leaked more than one million fingerprints and facial images stored in plain text on an unsecured server.

These incidents demonstrate the scale of the risk: once disseminated, biometric data cannot be replaced. Unlike a password, a fingerprint or a face cannot be “reset”; fraudulent reuse is therefore always possible.

The repercussions extend beyond the individual sphere. At the state level, national biometric databases, passport files, ID cards, and police data are highly strategic targets. Their compromise could be used for espionage, political manipulation, or blackmail. A country whose national identity database is hacked exposes both its citizens and its entire trust infrastructure.

Added to this is a more insidious risk: complacency. Biometrics enjoy an image of near-absolute security, leading many organizations to deploy them without thoroughly analyzing their limitations. This perception of infallibility fuels widespread adoption, often without sufficient control over encryption protocols, storage conditions, or access management.

Finally, the issue of biometrics raises major societal challenges. The collection and centralization of bodily data can contribute to a shift toward widespread surveillance. In the event of a leak, this information could be reused to track individuals, identify protesters, or conduct behavioral profiling without consent. The consequences of a breach are therefore not limited to cybersecurity: they threaten privacy, freedom of expression and, more broadly, citizens’ trust in public institutions and security technologies.

Come back in mid-November for the second part of our article on prevention and best practices for biometric data. In the meantime, if you have a movie, TV series, software, or e-book that you want to protect, don’t hesitate to call on our services by contacting one of our account managers. PDN has been a pioneer in cybersecurity and anti-piracy for over ten years, and we’re sure to have a solution to help you. Happy reading, and see you soon!

Share this article